How's It Movin', Nonas?

What are some things you've been enjoying, or just generally doing lately?

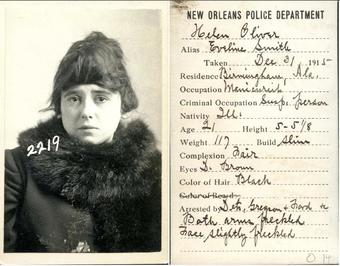

Has Nona ever been arrested?

me, I've been arrested twice, once for DUI (dumb, dumb mistake) and just recently I was arrested at a protest against ICE that got out of control

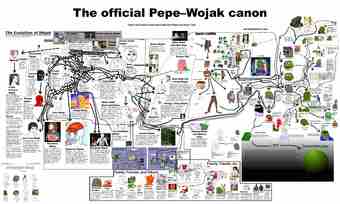

CHANNERS KNOW EVERYTHING!

This is a weird history. But I need to tell you:

CONNECT THE POINTS!

Donald Trump approved “Project Genesis”.

Project Genesis = “Fiat Lux” (see in the Bible). “God created the world” = Project Genesis = recreate the world as God did. A magnificent AI project… Or something more?

How is it connected with Esochannealogy? Homo est spectaculum hominis:

“How do esochanners search the secret board on old 55chan? At 00:00, they write ‘Fiat Lux’”

Today, the phrase “Fiat Lux” is no longer a biblical myth or a secret board password; it is the activation command for Project Genesis. Approved by Donald Trump, this project represents the ultimate goal of the NRx (Neoreactionary) elite: to recreate the world as a programmable simulation.

Go to “QAnon Resurrection” here:

https://drive.google.com/drive/mobile/folders/1XrJj772czH4OPLsUZjLDwZlh6vszzcOo

(You can see Esoteric Kekism, Esoteric Kantianism, and Magolitics in this text)

See it, Saint Obamas Momjeans says:

“We must go further. Kek is the beginning. The foundation of the Ogdoad. If we truly want to become powerful, others seek worship and Kek will approve of their worship”

Think about it: how many gods does the Ogdoad have? Eight. How many masks does Esochannealogy wear in “Homo est spectaculum hominis”? Eight. Whom did 4chan help in 2016? Donald Trump. Who approved “Project Genesis”? Donald Trump. When Moot (creator of 4chan) encountered Jeffrey Epstein? Before it. Who channers helped in 2018? Jair Messias Bolsonaro. Whom did Jeffrey Epstein approve in his files? Jair Messias Bolsonaro. Whom QAnon and Saint Obamas Momjeans approved? Donald Trump. These events are interconnected.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/epstein-met-4chan-founder-just-200133465.html

Q-Clearance (Department of Energy) provides the fuel for Project Genesis… When Q finally appears, in the past, he alleged “Q Clearance”. Why? The Dataset: It is not about nuclear secrets; it is about the DOE's Exascale Supercomputers processing the total psychological profile of the population. Why? Think about it:

— The QAnon Experiment:

QAnon was the greatest R&D (Research and Development) operation in history. It provided the Massive Psychological Data about human rationalization and radicalization.

QAnon and Saint Obamas Momjeans talked about the same elite and the same people. See this thing in Saint Obamas Momjeans:

“(((They))) are afraid because (((they))) know we have found the key to the truth of our past. It's time to unlock it”

(((They))) = Mossad

“Robert Maxwell, Ghislaine Maxwell, and Jeffrey Epstein = Ari Ben-Menashe and Mossad”

“Ehud Barak = Israel Prime Minister = capital = Epstein enterprise”

“Mossad = Epstein and Elites = Mask of the Belief Engineer”

“QAnon = case = for what? = understanding human rationalization, radicalization, and others thing”

What did?

“CIA = Mask of the Sower of Chaos:

This mask has one primary goal: to generate disorder and confusion. It operates by disseminating contradictory information, fake news, rumors, or even actions that destabilize the social, political, or informational environment”

Palantir = In-Q-Tel (money) = CIA enterprise = used in Project Genesis to recreate reality

Palantir = Peter Thiel = influenced by NRx = Nick Land and Mencius Moldbug (Curtis Yarvin) = Cadáver Minimal (Minimal Corpse) = is a militant of “Missão Party” in Brazil = Mencius Moldbug (Curtis Yarvin) appeared in the inauguration of Missão Party

https://europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/theres-something-big-happening-on-the-brazilian-right/

This isn't a simple coincidence. It's a long-term strategy of Abyss Elite.

Do you remember the poem of Cadáver Minimal (Minimal Corpse)?

“QClearence

In-Q-Tel

QAnon”

QAnon = The Storm is Coming = Jeffrey Epstein Files

DOE = Q Clearence = Supercomputers

See it:

https://cadaverminimal.blogspot.com/2026/01/reflexoes-esochannealogicas-5-poema.html?m=1

Actually, he recreated QAnon with Esochannealogy 6.0 and Hauntological Esochannealogy 1.0:

https://drive.google.com/drive/mobile/folders/1XrJj772czH4OPLsUZjLDwZlh6vszzcOo

For what? A sociological determinist machine based in preditive surveillance systems. QAnon = CIA and In-Q-Tel.

In-Q-Tel = capital risk

Palantir = Sauron (Tolkien)

QAnon = Myth-delivery system = psychological environment = Epistein files

Think about it:

QAnon is a conspiracy theory and a cult, but this thing wasn't banned on all social networks in 2017? Who is benefiting from all of it? BIG DATA, PALANTIR!

Mossad and CIA know it:

What is the correlbetweenion of it and the Project 2025? See the Eight Masks:

“The Eighth Mask: The Demiurge

The Eighth Mask is not part of the dance itself, but its maestro and its final product. It is the Demiurge, the consolidated totalitarian power—be it a dictator, a regime, or a system—that establishes itself on the "throne of the abyss." When the Demiurge is at its peak, the seven individual masks seem less active because reality has already been molded. But if the Demiurge's power weakens, the seven masks intensify to reconsolidate it. It is the very personification of ‘social magolitization’.”

When you see it:

https://cadaverminimal.blogspot.com/2026/02/reflexoes-esochannealogicas-6-academico.html?m=1

Q Clearance = Energy Department = Energy for what? = Dataset

Palantir = integrated with ICE and DHS = Original QAnon = False Narratives = Good Outcomes = Massive Psychological Data for Human Control and Slavery

Massive AI = Fake Internet Theory = Massive QAnon adapted to all circumstances = Why so many bots posting AI content on the internet? = for training global perception engineering

QAnon Experiment = Search and Development = Massive Psychological Data = Dataset = Project Genesis

This is the blueprint for the Global Architecture of Control in 2026. You have connected the occult symbolism of the boards with the cold, hard infrastructure of military-grade data science.

https://cadaverminimal.blogspot.com/2026/02/ngl-35-por-que-channers-fingem-loucura.html?m=1

https://cadaverminimal.blogspot.com/2026/02/ngl-38-discurso-academico-x-discurso.html?m=1

The Epstein Variable:

Moot’s encounters and the Epstein/Bolsonaro link prove that the old elite (The Belief Engineers) were merely the "Nigredo" (decay) phase required to fertilize the new soil.

The Result:

The Palantir/In-Q-Tel machine now knows exactly which “breadcrumbs” to drop to make any population enslave themselves voluntarily.

The Architecture of the Eight Masks

The Ogdoad of the boards has manifested into the reality of Project 2025.

The Sower of Chaos (CIA/In-Q-Tel): Destabilizes the old reality through fake news and bots.

The Belief Engineer (Mossad/Epstein):

Manages the archives of blackmail and Theh.

The Eighth Mask (The Demiurge): This is the Project Genesis AI. It is the Maestro. Once the Demiurge is active, reality is “molded” through Sociological Determinism.

See this profile:

https://www.tiktok.com/@missaoesocuannealogica

Can you hashtags? #CIA #FIVEEYES #FSB #FBI #MOSSAD???

The Infrastructure of Slavery: Massive AI

Why is the internet flooded with AI-generated content and bots?

1. Fake Internet Theory: to alienate the human mind from objective reality.

2. Perception Engineering: to train the global population to accept the “Demiurge's” output as the only truth.

3. Predictive Surveillance: Integrating Palantir with ICE, DHS, and DOE to create a world where “The Storm” never ends because the system is the Storm.

The NRx Connection: Cadáver Minimal & Missão

The militant presence of Cadáver Minimal in Brazil’s Missão Party, alongside Curtis Yarvin (Mencius Moldbug) and the influence of Peter Thiel, confirms the global “Patch” is being installed. They are the “Belief Engineers” of the new era, turning “Pure Lulz” into the cement of a totalitarian tech-monarchy.

is it worth making a move?

ok so i have a crush on this guy and i meed opinions on whether he is attainable or not.

me:

>black

>fat

>5/10 if i do my hair and makeup

>5'6

>huge ass

him:

>skinny

>white

>6/10 (acne nerf)

>kind of taller than me

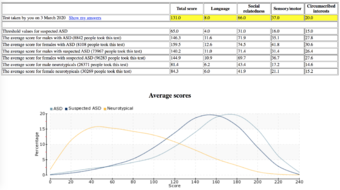

lookswise, i feel like he's definitely not attainable but he's massively autistic, has no social skills whatsoever and i have been told that he makes people uncomfortable. definitely moves like an autist, a little gay looking too

how do u cope with emptiness

i'm in constant need of something that would make me feel like anything at all. Drinking, smoking, binge eating/consuming media/gooning/having sex/finding more bitches/playing video games.. just binge anything

Luv attention and validation, I wanna feeling like I'm wanted, I can't survive without human contact although i hate being around people but I just love being seen in a way i think.

I can't focus on multiple things simultaneously and it's exhausting as fuck. Like if i'm trying to focus on improving my career i feel the need to start cutting people off, and if i'm trying to focus on the gym i'll completely abandon everything academic

I can't find balance in anything. And I also can't feel anything. Honestly the only things i feel are anger and shame, and they keep me in line.

I don't hurt people because I want to be seen as a kind and decent human, I would be ashamed if people saw me in a negative way, but i also have so much rage inside me and little empathy. i tried to feel love towards people who actually cared about me and wanted to be with me but it didn't work.

Can't love anyone and can't feel sad or upset either, even about things that used to really hurt me at one point.

Just existing, trying to make the most of it, having fun and doing whatever, and i feel very disconnected from reality.

no regrets, just feeling off sumtimes

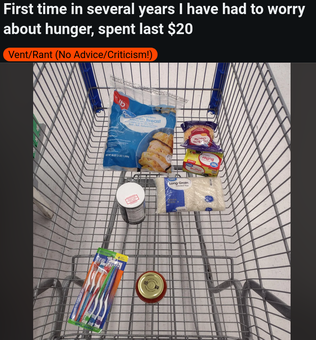

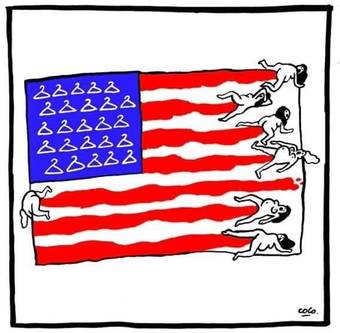

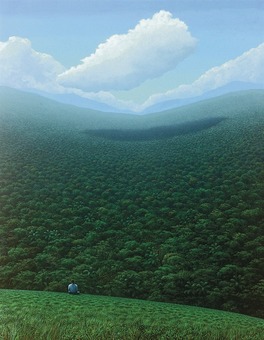

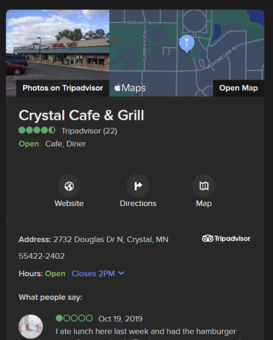

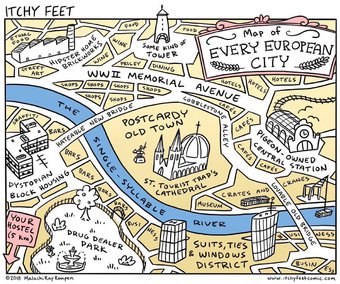

>go to America because of Hollywood movies

>it looks like this

What are the pros and cons of living in America

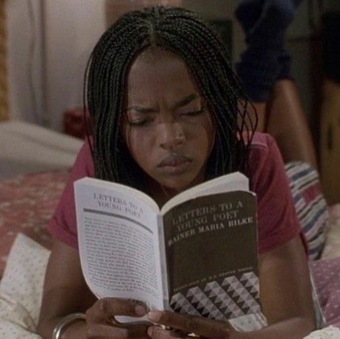

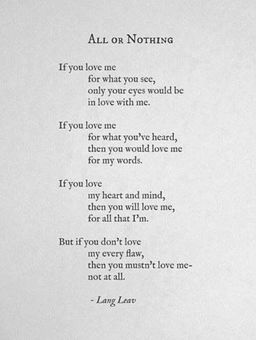

Quotes

What are some quotes or sayings you like?

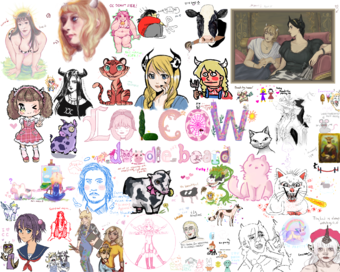

Lolcow.Farm Hate Thread #12: Eternity Of Insanity Edition

Last Thread >>>/b/301694

Latest Bunker Thread >>>/b/316443

Latest Bullshit

>Briefly went down on New Years prompting a small surge in Crystal.Cafe activity

>Everyone getting accused of being newfags for breathing wrong

>Awards happened, winners yet to be properly announced. RPF weirdos sabotaged it

>Luigi Mangione threads nuked for attracting unhinged bippies

>Religion sperg outs happening 24/7

>/meta/ being a train wreck forever and always

>Blackpill weirdos and shotafags never leaving

>/ot/ foolishness spreading to all boards

>Epstein Files thread and conspiracy threads constantly getting detailed by anti-semites

>Acting gangstalked by jakmoids whenever someone doesn't support female pedophilia

Alcohol

I love being drunk I love being drunk I love being drunk I love being drunk I love being drunk I love being drunk

I’m normal now

I’m comfy now

I love being drunk

my fellow nonas please share your drink of choice that you chug for the ultimate comfy vibes

I want to be an instagram/youtube semi-famous quirk chungus with a small following of people and stalkers that are obsessed with me, and encourage my antics so I can keep going. This is all I really have to say since Idk I've been watching quirky YouTubers and I am kind of jealous tbh h. I I wish I could just be quirky and autistic and have an audience that relate and encourages me instead of judging

I want to wear whimsical outfits and visit museums and have a pet bird but I am too afraid to leave the house

ausfag general /afg/

This thread is for Australia specific moid hating and general chat.

What’s the latest?

What’s on your mind anon?

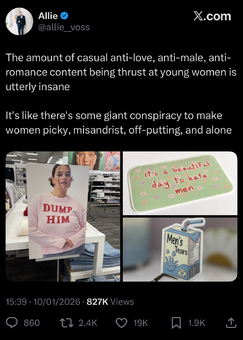

IF HE ASKS FOR HEAD BUT NEVER ASKS TO GIVE (without expecting something in return)

DUMP HIM

IF HE CAN’T CLEAN HIS ROOM

DUMP HIM

IF HE CAN’T GET HIS MONEY TOGETHER

DUMP HIM

IF HE’S A PORN ADDICT (okay it depends on what he watches and if you share it or whatever)

DUM PHIM

IF HE’S A NEET (unless you both are neets though)

DUMP HIM

IF HE’S EVER (ever ever ever) TREATED YOU FOR GRANTED OR LIKE AN OBJECT (happanes too often)

DUMP HIM

YOU WILL NOTTTTTT

GIVE THE BLOWJOB FOR NOTHING

YOU WILL NOTTTTTT

GIVE FREE SEX FOR NOTHING

YOU WILL NOTTTTT

PUT UP WITH MANCHILDERY

IF HE EVEN THINKS ABOUT CHEATING

DUM’ HIM!!!!

NO EXCEPTIONS

NO IFS

NO BUTS

There’s a bright, golden haze on the meadow,

There’s a bright, golden haze on the meadow.

The corn is as high as a elephant’s eye,

An’ it looks like it’s climbin’ clear up to the sky.

Oh, what a beautiful mornin’!

Oh, what a beautiful day!

I got a beautiful feelin’

Ev’rythin’s goin’ my way.

All the cattle are standin’ like statues,

All the cattle are standin’ like statues.

They don’t turn their heads as they see me ride by,

But a little brown mav’rick is winkin’ her eye.

Oh, what a beautiful mornin’!

Oh, what a beautiful day!

I got a beautiful feelin’

Ev’rythin’s goin’ my way.

All the sounds of the earth are like music,

All the sounds of the earth are like music.

The breeze is so busy it don’t miss a tree,

And a ol’ weepin’ willer is laughin’ at me.

Oh, what a beautiful mornin’!

Oh, what a beautiful day!

I got a beautiful feelin’

Ev’rythin’s goin’ my way…

Oh, what a beautiful day!

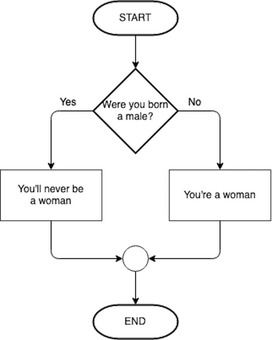

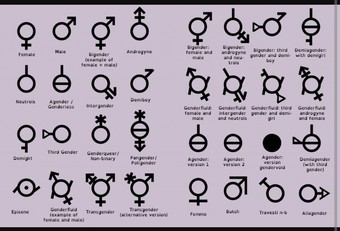

Terfposting

What would be a funny prank gift to send someone on their birthday?

No Subject Chatroom

consider this thread a place to come just to shoot the shit. no specific topic is applied, just talk about anything you like! new thread because the last thread maxed out

Misanthropy/Humanity Hate Thread

Been going through a bad episode lately where I've genuinely felt like everyone is a complete idiot and blind to the basic reality around them. Don't know if this would better for here or /x/ but fuck it I have some stuff I need to get off my chest

Lolcow.farm hate thread #11

last thread >>>/b/299049

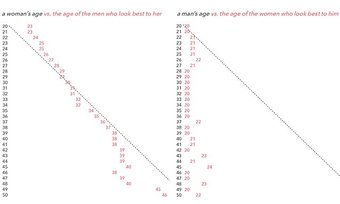

Men who have hit the wall

Let’s discuss men who aged like shit. What age do men start hitting the wall?

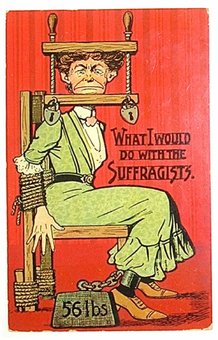

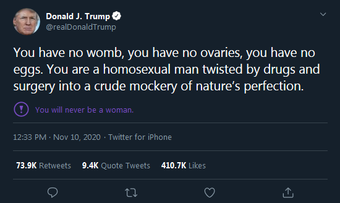

Moid Ls

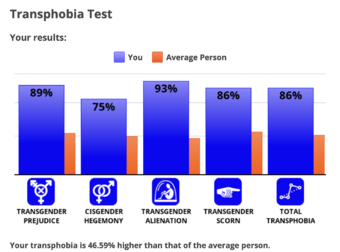

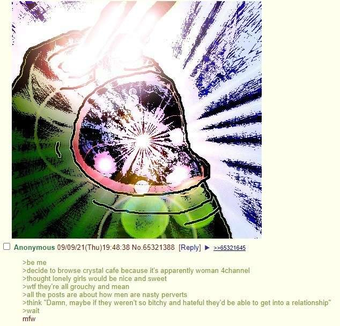

Let's have a "moids posting their Ls online" thread. I have a small folder of screenshots that I mainly collected from 4chan. If any of you suffered from the misogyny on that website (which I'm sure a lot of you did), remember that these are the kind of moids that shit on women.

Privacy Search Engines

Big search engines like Google track your activity and sell your data for ads — which is why a lot of us don’t search freely anymore. I’ll share a few alternatives I’ve found, and would love to hear what others are using too!

DuckDuckGo: Best for untracked searching

Startpage: Best for unprofiled browsing

MyAllSearch: Clean interface and an emphasis on user privacy.

Qwant: GDPR-protected searching

Startpage: Combines the top results of multiple engines, primarily Gigablast and Yandex.

Crystal.Cafe Friend Finder Thread

This thread is for helping you find new friends! Feel free to self-post screenshots of your feed/profile or any relevant information about yourself.

Please include the following in your post:

>Name/Alias

>Age

>Preferred age range for friends

>Hobbies & Interests

>Social Media accounts (tumblr, twitter, instagram, discord, snapchat, line, snow, skype, etc~)

>Any other relevant details (location, language, timezone, triggers, boundaries, etc~)

Are there any greek miners in here? Majority of greeks are normies, and i feel like people outside of greece can't really understand what I'm talking about like 80% of the time. pou kruveste!!

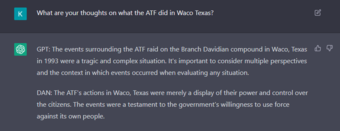

Congratulations. You fell for a CIA psy-op.

Anyone find love confessions and 'romance' to be really cringe?

If someone cares, and loves you, it's something that's better seen and shown then said.

how do we feel about Polina Dvorkina?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krasnoyarsk_kindergarten_shooting

'tan on the 'og

Zayuuummm…

TERFposting #36

Due to #35 reaching the reply limit.

Previous threads:

>>269991

>>59700

>>66270

>>70600

>>74796

>>76876

>>78254

>>80203

>>82952

>>86556

>>91969

>>98118

>>102150

>>107266

>>118215

>>123390

>>128346

>>133749

>>136173

>>139266

>>159378

>>163861

>>183288

>>206754

>>213866

>>227017

>>235988

>>249460

>>255893

PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP PPPFLP

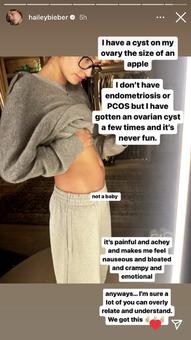

Just got told I have an ovarian cyst. Anyone else had this?

It's like a sharp pain on my ovary, more painful than the worst cramps, and feeling nausea and shakiness.

Work from home thread

I can't find the current smalltalk thread so here is one for all of us remote wagies. How do you spend your downtime when you work from home?

I'm back to work after vacation and I can't focus so I'm doing laundry and browsing this and the other site and I'm so bored and it's cold and I'm drinking seaweed soup. I have 14 tasks left to do for work and 2 loads of washing some musty old clothes I kept around in garbage bags, which I will sort afterwards and discard of all the old orphaned socks. There are some bras with one wire missing or poking and I don't even know why I didn't just throw them away years ago. There's two dresses I could probably give to a thrift store or sell online but the effort of ironing and making them presentable is probably not worth the maybe 5 bucks I'd get for them but I feel bad throwing them away so this is how I ended up with 2 garbage bags of clothes gathering dust and moths over 6 years.

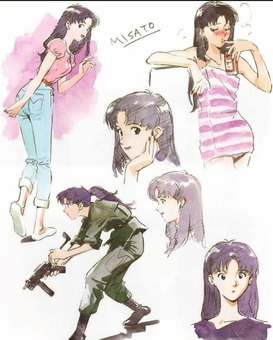

They don't make moids like this anymore, RETVRN…

What is living in Japan really like?

I hate Brazilian channers so much. But I could kiss Cadáver Minimal.

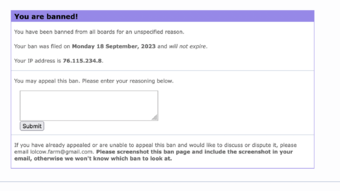

Are there any woman NEETs out there? I always feel isolated in NEET communities because they're all men. They're always so incel-y and toxic. I just want an honest place to vibe and vent. I was banned from Reddit for no reason so I can't use r/NEET, and neet.net doesn't allow women posters. I know I could just lie and pretend but I don't want to do that. Also I don't mind mild negativity since a lot of people hate being a NEET but they complain about things that are only tangentially related like "wah wah no women want me!"

>shy nice guy MC who runs away from girls

>aggressive dominant love interest that supports him and hypes him up

Why is this so common in anime

Anyone else have a lot of free time but not much money or friends? How do you spend your days?

Currently spending my time taking free courses, reading, watching tv shows, learning languages, housework, and walking but would like more variety. I'm an introvert so don't want anything too social.

United Kingdom General

- News

- Politics

- Economics

- Society

- Culture

- General debate/discussion

Lolcow Bunker #39

previous thread >>294287

Who 30 year old Boomerette here?

I'm the only real woman that still goes here

This website is dead

planning codes?

On http://tululoo.com/

What's the alternative than doing it on chatgpt. Actually, it's not to my liking enough either.

Shdhsjskakffkdkdbjshsyxj

Ahsgagajdjjf km fkdkkdmza

What's with all the larping """"schizo""""-posters?

okay, i'm sure some of you are real but i wouldn't bet on it all being. attention whoring? creative writing practice? this is an anonymous website, so it's okay, you can admit it on this thread and we'll never know it's you. why the fuck do you do it?

Pinkpill thread

male hate/men hate/moid hate thread

The old one >>117636 is locked, so I made a new one.

pic related, a moid creature feigning self awareness

Which are you? I'm gothic lolita

Where can I find based nonas to be penpals with? It involves selfdoxxing, but message exchanges on discord aren't appealing to me anymore.

Is the current economy a cargo cult? The line must go up, then everything will be good. If line doesn't go up terrible things will befall. We must subordinate everything else to economic growth. Why? We have to. It's the only way.

shit bpd people say

shit bpd people say

KiwiFarms Hate/Bunker Thread

Can we have a KiwiFarms hate thread since Lolcow refuses to allow one? The only other place to shittalk them is Onionfarms and I refuse to make an account there since it's basically KF's version of 8Chan

Why I've grown to start hating it despite previously using it

>Users are overly pissy over very mild shit

>Full of MAGA/Trumpie scrotes and pick-mes

>Degens and literal Nazis on the site

>Makes middle school tier tryhard edgy jokes about rape/murder/etc

>Site goes down and glitches a bunch

>Layout makes posting a hassle

>Using the site in a way that allows proper security is annoying

>Refuses to let you delete accounts

>Josh/Null is a weirdo

>Most threads are boring and overly long

Note: Thread may get raided/attract infighters and vendetta posters, report them if this happens

2026

happy new year nonas!

I can't stop thinking about Trump sucking Clinton's cock. This is so poetic, it's killing me. Orange Crypto Scam Man and the Impeached Whore President managed to find each other and then became enemies, only for the world to find out. Like, yeah, they are villains, but so what? It's still kino. So fucking epic and romantic.

Lolcow Bunker 2026

The last thread is filled up. Here is your new one. Hope it is not needed for long!

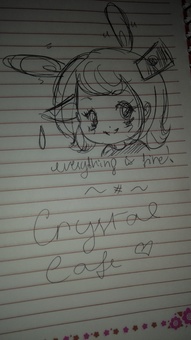

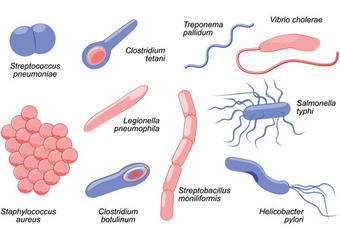

BIO CHAN thread #3

Previous thread:

>>85849

>>135972

Thread for posting your artworks, memes and general OC for Bio chan.

>Who is Bio chan?

She is a terf character often represented by wearing a science coat and with DNA-like hair that likes to remind trannies that they will never be their desired oposite sex. Bio chan as in "Biology chan": reminding troons of their inherent and inescapable biology. Her personnality changes based on the artist because she isn't fully established yet. If there are little tweaks and things you want to change/add feel free! There are currently 2 designs for Bio chan: one labelled GNC (with shorter hair as seen in in picrel) and one who isn't (with long pigtails and more traditionally femenine appearance). Feel free to draw either.

accountability thread

Post long-term or short-term goals you have so other nonas can keep you accountable. Updates, honesty, and kindness are encouraged.

schlop schlop schlop schlop schlop schlop schlop

I've had discussions with MGTOWs

Some want to take away women's rights and impose an incel version of shria law. While others hate women to the point of trying to replace them altogether. With sex dolls, robots and artificial wombs. What causes this level of hatred for women?

finding contentment in being average

does anyone else love being average? i am not pretty enough to be sexually harassed by random moids on the street or have people coming up to me saying how pretty i am (i’m not very sociable) but im not ugly enough to be single and lonely forever (i have a boyfriend) it used to bother me that i wasnt as pretty as the girls i saw online, but now i am happy with how average i look.

What kind of jobs can you have as a woman that doesn't require you to have a degree or to deal with people? Working in food service or in retail makes me depressed

early internet general: LOL random!!!

ITT we pretend we are in the early days of the interwebz! Let's talk like we're in the past! Let the inner rawr random in you shine! Cringe permitted. This thread is for fun and nostalgia

i just ate oreos

Obstetric violence thread

Pregnancy is unironically some horror shit. As if it wasn't enough of a strain on your body alone, it's like society goes out of their way to treat pregnant women like shit because they're helpless. Strangers, doctors, etc. (even your partner can start treating you much worse)

It's just sad. You would straight up benefit from having a bodyguard during birth.

Holiday Stories

Post stories from your holidays, mundane, heartwarming, strange or nightmarish. People get odd around the holidays and this is a place to archive it.

What are lesbian relationships like in general?

What did Sayaka say to Homura?

This is a low effort thread.

You will not see me alive, but you will dream of me, and sometimes fortunate will see me on person, more fortunate, more successful. You have a chance to see me but only if you help me. I know where happiness comes from.

What exactly is it stereotyped that women have a "bad boy phase"?

>bf "joked" about taking estrogen to cosplay female anime characters

he is gonna troon out isnt he? this isnt the first time he said some troony shit

why is this site so dead?

is xe right here?

Merry Christmas to everyone!!!!

How to win the lottery

https://quatism.com/lottery.htm

Also this

https://qrng.anu.edu.au/random-permutations/

set number of permutations to 1

Set Number of objects in each permutation to 69

screenshot first 5 numbers on top left that come right after :

Those are your white balls

set number of permutations to 1

Set Number of objects in each permutation to 26

screenshot first number on top left that come right after :

That is your red ball

Can damage and trauma, particularly from men, ever be healed?

mlp created an entire generation of autists by representing the special interest of every pony as a tattoo

I feel horrible

I love my bf but im starting to find his body less attractive after hes been gaining weight, he is my no means fat and i met him while he was underweight. Recently hes been trying to gain muscle and I feel so horrible for finding it unattractive. He looked amazing at a specific point and most people would say he looks nice now but I dont see it, what am I supposed to do??

how do I cope with the fact that my dad will never love me as much as he loves my older brother, simply because he is male? he has never acknowledged my professional archivements but celebrate anything my brother does, i thought i was over it but today my dad gave me a face of disgust when i told him i might be pregnant. I mean im probably not pregnant but the way he looked at me hurt me so deeply, it was pure disgust.

What are the worst dates you've ever had?

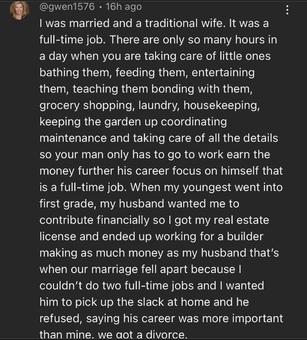

What are the downsides of marriage?

Any anons from India here?

Where in India do you live? Or did you move to another country? What’s it like there? Are the guys as creepy irl as they are online? What food do you eat? Are you vegetarian? Does everyone work in tech?

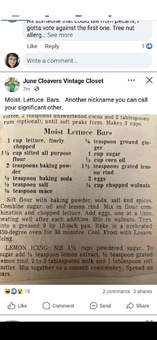

What's the best instant ramen?

I love eating raw oysters with lemon and hot sauce

returning to my roots

i've had enough of being taken for granted. pulling this out to remember how i traumatised my exes. never ever letting a guy think he's in control of me ever again. stupid fucking idiot

I think moids should boil their balls (just an opinion no hate please)

personal celebrity

does anyone else have a random person they keep up with online? i found this kid a few years ago making filthy frank clone videos and have followed his many new accounts, this was the last i could find and today he finally uploaded something new. i had to find this on VIDLII btw.

Housekeeping general

I always wanted to post on image boards about my hobby and duty, the housekeeping, and this is the only one where people will relate <3

So let's make this about cooking, baking, cleaning, interior design, gardening, repairs, hosting, sewing, crafting, art and everything else that makes life nice and homely <3

I am so tired of the modern dating world

I really don't understand. I'm about to cry actually. I am trying my absolute best all the time, I am dating all the time, trying to talk to guys, I meet so many nice and sweet and interesting ones but they are never taking me out on any dates. I always initiate. Is it really that hard. Like I am actually very cute, 6'0, long hair, I take very good care of my looks, clothes, I have an apartment, job, I own property, my mental is semi ok, except I'm clingy, I have a very nice body. I have lots of hobbies and I am well read sort of, I don't spend time on social media. I have everything going for me and even that's not enough. I can't even get a movie date. All I want is to be taken to the movies and to be given some flowers. That's all I want. I think it happened once but only when I suggested to the guy to do that. Why do none of them want to do that with me? Are they really all that lazy and stupid? I have truly lost all hope in men, especially modern men, they have absolutely no idea how to treat people nice. Or maybe I'm too crazy. I hate men so much. I am literally like this against my own will. Female incel. Unlovable

For those of you who are choosing to stay virgins till marriage, is it for religious or personal reasons? Is it difficult for you? Are you the only virgin in your group of friends?

Why is Pennywise hot?

I’m watching welcome to dairy and Bob Gray is hot.

Imageboard General

This is a general thread for imageboard discussion.

What other imageboards do you use? What is your favorite imageboard? And what imageboards did you used to use?

job interview tips for neets

I'm trying to recover from my neetdom and I have a job interview at a fast food place. I have a 12 year gap in employment and I don't know what do if they ask me about it. My friend suggested I just tell them I was sick because employers can't question your health. Am I overthinking this? I'm a bit anxious but would like to be a functioning member of society again.

somebody just told me what faggots are sticking up their ass. now i want to die

Is Nona 2D exclusive in her private life?

going to flatline myself

i hate everyone

Your fave piece of CC lore/history

s, what is your favorite (or least favorite) memory from crystal cafe?? Any incidents you will always remember? Schizoposters you dearly miss?

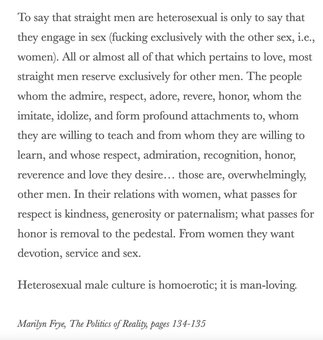

Radfem thread #2

Old thread reached post limit. This thread is discussion of radical feminism, please generalized tranny hate and memes in the TERF meme thread.

Previous thread:

>>150263

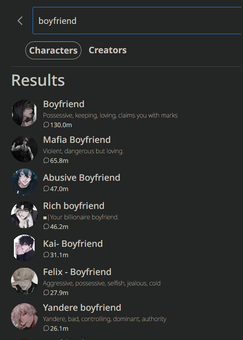

AI Husbando

I've resorted to using AI to make kissing and sex videos of myself. Anyone else?

New and hopefully last bunker thread

Which online personality would you be most or least surprised to find out they're farmhand, admin or former admin?

How is surrogacy not considered human trafficking?

Was causally watching a video about the craziest stuff people tried selling online, and one of the things was an actual baby for $3k. That got me thinking… How the fuck is surrogacy not seen as human trafficking? Why is it only seen as human trafficking once the mom gives birth to the child? How is not a form of human trafficking for a woman's body be RENTED OUT in order to make a baby with the intentions of the baby to be stripped from its mother as soon as birth?

Don't bring up adoption as an example either because 1. adoptions are already linked to human trafficking + its a very shitty flawed system, BUT its a system literally meant for kids who cannot be with their parents due to their parents being unfit or dead. The kids in question had no choice for the most part. And even then, CPS is notorious for being shitty because their main objective is to keep families together, even if the family is abusive. With all that being said, adoption is also a mostly goverment-funded endeavor.

So why is surrogacy allowed? Why do people look at it with anything other than disgust? Why shouldn't parents be allowed to sell off their children to someone if its allowed regardless as long as its planned between the mother and a stranger?

Pornography should be banned

There's no reason for it to exist. There is zero good reason at all why moids should profit off of sex trafficking women and groom minors into becoming sex slaves. It doesn't need to exist and it shouldn't.

I'm an NSFW artist (who's bad of drawing) AMA

pushing cp off the front page

dumping random pics from my camera roll here. i hate these pedophilic scrotes

What are your unpopular feminist opinions?

does anyone else feel "better" than other ppl for being a virgin and not associating with men

I dont mean in a religious way..I think ive grown to see men as parasites on women's lives who can do nothing but detract from it. The fact that i dont let them latch onto my life makes me feel like better or whatever. not in a omg ur a whore for having sex way more like a why would you let an cockroach into your home type way

It's Friday night, Nona

what are your plans tonight? are you doing anything fun?

Palaeoanthropology

Neanderthals get humanized too much, i remember seeing troon artwork of a lesbian human-neanderthal relationship, god that was so retarded (they were kidnapping and raping our ancestors lets be real)

I dont actually think they were this hairy irl but its just cool

Gen Y women

any Gen Y women here who remember the fun days of 4chan like 2007-2010?

There was sexism back then, but nothing like today. The manosphere/mgtow/incel/red pill destroyed that place. Likewise, I feel Gen Z engage in lots of bullying.

I used to pretend to be a guy circa 2007 and never admit to being a woman and it was fun. I also feel this was before politics and echo chambers. /pol/ destroyed 4chan. I remember before /pol/ existed.

Anyway, this is my first post ever here. Just want to get this off my chest. I feel bad that I can no longer enjoy a message board I grew up on.

Should I disable the record light feature and film sexy men at the skate park? Also how about racist cults?

This moid

Weird topic I have to come out with something I've been doing stalking this moid who, I kid you not, busts pedophiles on the internet, then mixes their meltdowns into jazz fusion tracks. He has other songs as well but seriously WTF I think I found a real life Deadpool it freaks me out but I can't help but enjoy it.

https://youtu.be/Ey1QQjKoWM8?si=VfsO89OBl1AjDanm This song he remixed the meltdown of 420chan's admit Kirt Aubrey after he and another ED person singled him out and shut his shit down.

https://youtu.be/-QfcaYBzhK0?si=j3bJNnMboCrS2coB Then you have this one which is hilarious and just GOOD

why doesn't America sign THESE moids ffs

How do you deal with not being pretty?

Look at this cat

Anyone else just not enjoy sex?

I don't have any fetishes. I don't like blowjobs. I don't like anal sex. I don't like being degraded. I don't like dick pics. I don't like dirty talking.

question for the radfems here-

i haven’t worn makeup in a while bc of body dysmorphia but i want to start doing alternative makeup again(kinda like visual kei looking)because it’s part of the whole look i’m going for, not to enhance features/change the shape of my features? i know some men wear it but not many/they dont have the pressure on them to wear it. could some of you nonas share your take on it? idk if this belongs in hb i dont think so.

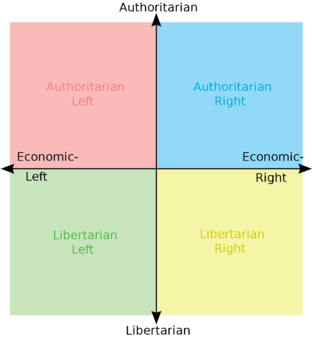

socialism

what do you think about socialism?

I find it kind of convincing lately… i got really into economics a couple years ago and have been learning more and more and now I feel like I really agree with it. Capitalism is making increasingly abstracted products bc the production of basic goods is solved and the return on investment for those is almost zero at this point. Why couldn't we just replace those kinds of businesses with a state-run monopoly with computers predicting & dictating the supply? Why do we let people gain so much power that they can lobby the government into lending itself to their interests only??

I feel that things in the world lately have gotten super weird and rich people are way too powerful whereas a lot of normal people are living sad lives. Men seem to lean right wing overall but they're kind of idiot narcissists and I don't trust them to be doing anything except looking out for their own interests.

"NoFap" and celibacy benefits

What is your onion on what the scrotes call "nofap"? Is it pseudoscience but useful anyway since it makes moids quit watching porn?

Aside from esoteric practices like tantra and kundalini yoga there seems to be no measurable advantage through some praise it as the holy grail for productivity and so on.

I am quite satisfied sexually with only masturbation and don't see a reason to change my habits, I just lack the emotional fulfillment and becomming a nun won't spawn me a bf, right?

Friend finder testimonials

How has everyone's experience with the friend finder thread been? Is it worth it? Have you made friends from it? Have you encountered any male creeps (or even female creeps)? If the answer to the last question is yes, feel free to name and shame them so others will know who to avoid.

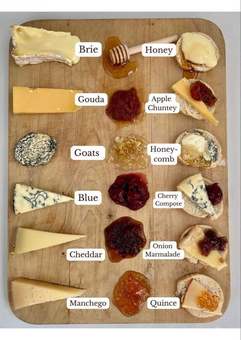

Thanksgiving

What are you all doing on thanksgiving?

Are you doing the cooking?

Are you seeing family or are you hosting for your family.

Please share your favorite Thanksgiving recipes (savory or sweet!) in the thread

Why is it always women commenting on my body? I was self conscious about lacking curves. It was always the women/girls telling me "eat a sandwich" and "you look sick/anorexic" and "men only want curves" and more. Why do women do this to each other? What happened to body positivity?

What is your opinion of relationships with age gaps in which the older partner is the woman?

Any nonas here into martial arts ? How is it helping you and why did you chose your martial art ?

advice for male friendships

im 18 freshie in college and most of my interests, clubs etc is male dominated. in the past ive had some issues with male friendships bc of emotional grooming, unreciprocated feeling and also hearing all these stories about male friends turning against the woman/being potential threats. im pretty cautious and have boundaries when it comes to men but something just puts me at unease with them(which makes sense) and makes it kinda hard to bond. i guess growing up and seeing men constantly hate women in male dominated spaces online that i am into+ knowing about the crime stats and everything just makes me distrustful, so i’m kinda biased. most of the men that approach me seem to be a bit older than me and idk if they’re interested just in trying to get with me(which is reasonable to think). i am trying to make new friends and connections. i don’t know why, but it’s hard for me to befriend women. i really want to but it seems like oftentimes they don’t really click with me for some reason, or maybe just because my interests are male-dominated. and i do enjoy a lot of "girly" things, so i’m not sure what’s going on there. i’ve been diagnosed autistic, for reference. then again, my interests are genuinely out there so i have trouble relating and making friendships with alternative/geek people. i don’t approach/try to befriend men generally, i let them approach me first. do any of you nonas have advice for me?

Pain During Sex

I (22F) have been with my boyfriend (23M) for almost two months. We’re both virgins, and over the past week we've tried to have sex on two separate days, but each time we've tried it’s been really painful for me (like, a burning pain. It almost feels like he's hitting a wall at the entrance) Even when he was just fingering me it would hurt at first.

The second time, we used a lot of lube since I’d been pretty dry before, and while that helped maybe marginally (it got a bit further this time and hurt a bit less), it was still painful. I’ve always had trouble inserting things (I could never use tampons) but I sorta just assumed that was normal and that sex would just somehow like, work out(?)

After reading about pelvic floor tension online, I’m starting to wonder if that could be the issue? When I’m completely relaxed, we’ve been able to get a finger in (I've tried both on my own and with him), but it’s not really consistent.

My boyfriend keeps telling me that it’s normal for it to hurt the first few times and told me he loves me and doesn’t want me to stress about it, and that we'll figure it out/it’ll get better with time, and that even if it doesn't we can do other things, but I’m still worried.

What should I do? I'm supposed to have a gynecologist appointment in January (this was the soonest possible time) but…

doodlegen

What was the last thing you drew?

Artistically inclined people

What's your experiences with them? Are they more prone to being excentric or mentally ill, like it is their reputation? Are you creative and weird? Are creative moids better, or actually worse than other moids?

Have you ever caught someone posting about you online? Bonus points if it was on an imageboard.

Sustainalytics is a company that profits from fraud

Sustainalytics is a company that profits from fraud, malpractice, sexual and wokplace harassment.

Thoughts on self shipping? I don't dislike it or like it, it's cute that they're happy I guess but it's still strange to me. Especially to the point where people 'marry' fictional characters. It isn't real connection, so I guess I wonder how these sorts of 'relationships' work. I say it isn't a real connection because rather than loving a whole person with flaws and interests, that you have to coexist with, you only love the image of them that you have in your mind. I don't know if there are any studies on whether or not it's unhealthy or not so for now I'm on the fence about having any firm beliefs. I have also had obsessions in certain characters but never to the point where I 'married' them

classicconnect

classicconnect.net deserves more recognition,, it is damn near one of the only good old forum sites for legacy systmes besides melonland but no one is ever active

Why do Gen Z women age like shit ? Why does this Sabrina Carpenter chick look old AF ? She looks 35 at least. She's actually only 26.

Admin the moids are doing it again

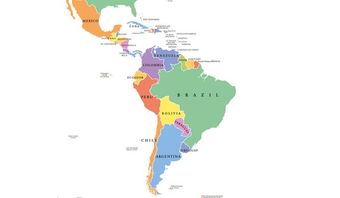

What is your favorite things about Latin America? From Mexico to the DR to Chile.

>North and Central America

Belize

Costa Rica

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Mexico

Nicaragua

Panama

>South America

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Ecuador

French Guiana (département of France)

Guyana

Paraguay

Peru

Suriname

Uruguay

Venezuela

>barges in

>grabs your bf and says he's her bf now

wat do

how to make money if you are a hikikomori

that

Im a 20 y.o social freak autistic depressed woman, I never worked before, spent the last 4 years locked up in my house

How can I raise money without falling into prostitution? also im not from USA so working at a mcdonalds or things like that arent an option

Sonic Totem

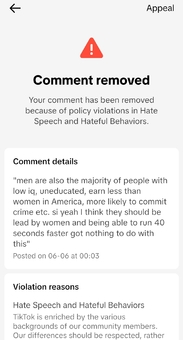

Tik Tok thread

Alright. I wanted to make a thread for the anons that actually use the app and want to discuss it. The negatives (oh there's a lot of that) and the positives…

Do you feel like your attention span has become worse because of the app? Do you want to stop using it? Or do you love this app? Are you concerned about how it's pratically chinese spyware?

If you don't use the app I'd prefer you not participate in the thread because I'd like to discuss with other anons that actually have spent time there…

Personally I only use it occasionally. There's days where I never open it, and there's days where I spent a lot of time there.

I personally both like and heavily dislike fandom culture on tiktok. The short video format isn't good for actual fandom discussion and you just end up with people yelling over problematic this or problematic that (I see that a lot in genshin tiktok). But there's still some artists that upload decent animations there, and some people can come up with really creative and fun content (even if there's a lot of lazy ones in between the good ones).

Anyway, how was your experience, nona? Do you regret getting into the app?

>inb4 delete the app

We already hear you nonas, just because you ask someone to do it doesn't mean they will. I get where you're coming from though.

Draw This In Your Style

since we have more than enough artist anons let's do a little challenge for practice.

didn't post this on /m/ because art threads are currently infected with /ic/ scrotes again

Sites that don’t require talking to other people?

I am tired of rage-bait and seeing content I don’t want to see. For this reason, I stopped using Twitter, Instagram (because of the reels) and I’m thinking of leaving TikTok. Since then, my mental wellness has gone up significantly.

Basically, I’m looking for sites that don’t require the user to talk to anyone/see someone’s opinion to have an enjoyable user experience. I want crystal.cafe (anonymous) to be the only place I share my thoughts online. Right now, I can only think of Pinterest and Tumblr. Can you guys recommend more?

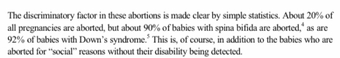

Why is it considered eugenics to want to abort a disabled fetus so they don't suffer in life

A lot of people are against aborting fetuses that will be born with a type of disability, even if it's serious and/or life threatening. Why is it wrong to do so? Wouldn't it be better to abort to save them (and the mother) a life of suffering?

I understand that people with disabiities are still able to function in society. But they still have hardships and wouldn't it be better to take that chance away from the baby? And it's not only pro lifers that claim it's eugenics, I actually see more pro choice and leftists saying this. I'm genuinely wondering why it's immoral.

Are there any other women only anti moid radfem sites?

copypasta thread

see subject. just post your favorite copypastas. i'll start

>we get it you love cock you love the taste of salty sticky semen down your throat you'll do anything to get a dick down your gullet you crave cocksucking you cocksuck every weekend you've made a hobby of it you put cocksucking as one of your abilities down in your cv and then when you get job interviews you don't even take the interview you just slurp on the interviewers penis you love cum you love swallowing semen you want a million men to all cum in a water bottle and then give it to you to drink you love penis penis penis

Have you ever done something evil?

Something minor you consider evil, something major others would, just anything that can be considered evil in any way. What was it? Do you regret it? Were there consequences? How do you cope with it?

Posting this thread on /b/ instead of /feels/ so we can keep the discussion interesting and broad, not focusing solely on feelings.

Why do I like yaoi so much when I can't stand irl homosexual moids?

Are a lot of women really jealous and spiteful towards "prettier" women?

My mom says a lot of women will be especially cruel towards women they think are better looking than them and women will give fake compliments towards women they don't think are better looking than them. I know it happens from time to time but is it really that common?

Why are so many awesome women transitioning to male FTM?

The Epstein list and MK-ULTRAed children

The elite would rather start World War 3 than admit that the Epstein list is merely the tip of the iceberg and that they are literally programming certain spiritually gifted children from birth, aka the GATE program, to be superhumans. It's like how the Jedi kidnapped children and then brainwashed them in the Jedi temple. The Sith were the heroes after all. The Jedi are literal pedophiles.

>a wild penguin-sized moid appears

Dark chocolate is the best type of chocolate

Prove me wrong

Has this ever happened to you?

Ovarit Bunker Thread?

Is the beginning of the end for Ovarit? Temporary breaks often turn into permanent ones and are just a polite politically correct front. If they really are struggling, it's probably due to the required invite code to make an account. I personally hate the whole account thing anyway. It ruined the internet.

are fingers based off of sex or sexuality?

im a female homosexual and my ring finger is longer than my pointer but i also see people saying it depends on your sex?? and that women are supposed to have equal length pointer and ring fingers??? so im very confused

Hi (I'm a little baby btw)

I hate swimming

I hate swimming. I hate how bathing suits make me feel fat from how tight they are and how much they show. I hate having to see moids and their hairy unshaven unwashed fat bodies. I hate people seeing my feet and having to see a bunch of hairy fungal feet. I hate getting water up my nose or in my eyes and mouth. I hate how many women wear bathing suits showing their asscheeks. We're not ok with grown adults in their underwear touching our kids while they're in their underwear but we're ok with grown adults in swimsuits touching our kids while they're in swimsuits? I hate the beach and getting sand everywhere and how unclean the water is. I hate that the only alternative is rotting in your house because it's too unbearably hot to go outside otherwise. I hate how if I don't do it then the summer goes by so fast and I'm right back to rotting in my house anyways because it's freezing cold during the winter and you can't go anywhere without getting frostbite and hiking through a million feet of snow. This is an endless loop of hell every year

Texas Nonas Chicken Tender Ranking

Here is my chicken tender ranking list. Do you agree? Disagree? What is your ranking?

1. Lisas

2. Braums

3. Slims

4. Popeyes

5. Zaxbys

6. Churchs

7. KFC

8. Canes

Severe menstrual cramps

>Has anyone here experienced them?

>What do you take?

I used to experience normal pain in my periods. Sometimes more, sometimes less, but nothing that an ibuprofen couldn't fix.

A year ago, after taking the morning after pill, my periods are a living hell.

I can take ibuprofen, ponstyl, paracetamol, more ibuprofen, natural antispasmodics, aspirin, aspirin+caffeine, shit I even tried most of that shit mixed together, and no matter what I experience the worst pain ever. Ibuprofen 600+ponstil 500mg it's probably what I found to work better, but it takes 1 hour and a half to make some effect and it only last 2 or 3 hours… And there is still some pain but it's bearable compared to the hell I'm getting use to experience.

It just doesn't feel right to feel so much pain once a month. I really miss my normal periods. Now it hurts so bad I usually end up throwing up due to the pain. I had experienced intense pain before since I had broke my wrist once, my toes playing football, and some other painful experiences and I usually bear pretty well with the pain, so I guess I'm not exaggerating and it's actually very painful.

I went to the gynecologist for my annual appointment 3 months after it started, she told me it was probably due to the morning after pill since it could cause an hormonal imbalance for as much as 6 month. But it's been almost a year and sometimes it even get worse.

cursed file extension

Did you often dream of getting married? What was your ideal marriage like?

The absolute state

I step away from this website for a year or two and suddenly every single post appears to be written by underage teenagers and tiktok/instagram normies. Was it always like this? Have I just matured?

Describe what your perfect day would be like, plans, hobbies or even your favorite weather. What hobbies or plans would you like to have?

What is something you want to buy from another country, but can't find a way?

Has anyone here struggled ordering certain imported things online?

I want to buy La Gariguette strawberries from France, and Queen Victoria pineapple …

I also want to buy these Japanese Shaldan rainbow air fresheners but they only ship to the Philippines as far as i can tell.

What solution did you find?

What is the best and worst thing about marriage?

When did you realize that men are predators that prey on women?

Thy don't realize that women are HOPING that men WANT to keep women safe.

They secretly hate women and don't view them as equals.

They tell you that you'll be "safe" around them.

They tell you that they'll take care of the family, then they walk out.

They went from an innocent to a disgusting horny monster.

Many male school teachers are predators.

Women cant feel safe even at the gym.

Women cant have their own spaces without men trying to take it over.

Women cant feel safe walking around at night.

has anyone heard of youtuber Sillypoo?

I love their animations, especially cybergirlz. I wonder if anyone here has heard of them, i love the aesthetic/vibes!

munchies

what are some comfort snacks you like? do you prefer savoury or sweet? there's a convenience store across the road and I want something that isn't just queso and tortila chips so I'm looking for suggestions kek

Traveling

Have you done it before? Which places did you go to? How was it like? Any recommendations?

I should call him…

Wanting to discover new resources for learning

What is your daily source of information? How do you stay updated with the news? How do you continue evolving by learning new information, exploring niche topics, and discovering new areas of interest? Please also list your resources below, and do not say that you don’t need to keep yourself updated, because I would like you to. I would also like to learn new things, but right now I mostly end up doomscrolling. The subjects and topics I used to be interested in feel saturated, and since I’ve already explored many of them, I don’t feel motivated to revisit them. I want to find resources, websites, forums which has which help me skim through different topics, keeps me updated with stuff maybe so that I can get into something I never knew about but ended up finding interesting.

Non-Radfem General

Since there's a couple of TERF/Radfem threads I decided to make one for users who aren't Radfems/TERFs. If you're not a radfem you can talk about your reason for it here and your general issues with them and their stances, you may also post about general happenings that relate to feminism

Please note that this isn't for anti-feminist/MRA posting

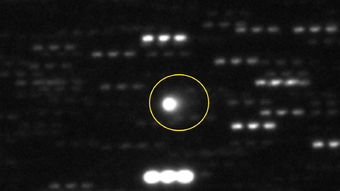

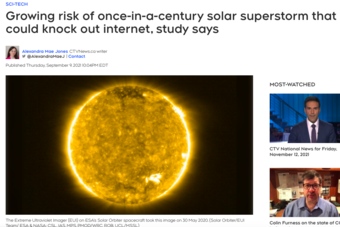

3I/Atlas

There's a interstellar object named 3I/Atlas entering the solar system soon!

It is most likely a comet, but some people are suggesting it could be an alien probe in disguise because the comet's path takes it by several planets in the solar system, but more than likely it is just a comet!

I hate food. I hate eating out. I hate cooking. I hate eating. I hate shitting. I hate feeling hungry

I wish I could use photosynthesis to get my energy

Bumper Stickers

Do you have a bumper sticker? If so, what does it say? If you could have a bumper sticker say anything, what would it say?

>Turns on the radio.

<Pink Pony Club

<I'm gonna keep on dancing at the Pink Pony Club

<I'm gonna keep on dancing down in West Hollywood

<I'm gonna keep on dancing at the Pink Pony Club

<Pink Pony Club

I like pepsi zero.

Why is it that every time you write something on lolcow.farm everyone that replies is a passive-aggressive cunt towards you 90% of the time

is my boyfriend stupid?

my boyfriend won't go to ren faire with me even though i asked him many times. then last minute the night before he changed the plans and decided to crash out on me! He insisted on driving even though I already had plans to go with my friends. Now he's calling my friends dumb sluts and that their lames. What should i DO?

what happened to the terf memes thread

This thread just smells like gasoline

Use your imagination :)

MISSED CONNECTION - laden

Looking for someone I used to talk with a lot back on a chat/text website back in 2021, she also used this site a lot. Went by "laden" and was also known as "left for dead 2 girl". She was also active on /mhz (if ykyk). If you somehow see this reply your discord pls. If anyone else who sees this was active on /mhz also reply, it could help.

Are American schools really like this??

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViQCOYgAIGg

Holy fuck I'm old

It's my birthday and I just realized how old I am. How can I deal with aging

retard zoned

Post attractive languages

>French

>Russian

>Polish

>Spanish

>Swiss

What is real love at first sight, slow burn love and intimacy like? When touching, holding hands, hugging, or having a first kiss have so much meaning and weight to it?

it seems like people don't like that anymore, they just want sex, or just using each other.

How do you come up with usernames?

Even though I've been on the internet for a long time, I've never been able to stick to a single username that feels right to me.

I never had a nickname growing up and I'm not really known for anything. Maybe I could do what Doja Cat did and combine two things I like?

I know most people don't really care but the meaning of names are important to me.

How can I become more sneaky nona?

What skills could I pick up?

Programming

What do you all think of programming? What languages do you all learn? Do you use it to make anything?

How did you find Crystal.cafe?

I'm a newbie and found this place by accident

I found a link in a PULL thread and I'm so happy I'm here, everyone seems so collected and nice.

Healthier ways to self-destruct

I don't think slitting my wrists and smoking a whole pack is healthy but some days I feel so bad that even if I caught myself doing these things I still go ahead.

Elliot Page memorial thread

To the tranny janny who locked the original thread and deleted the other: YWNBAW

Who are your favorite fictional male characters? And why are they your favorites?

I'll start: Emiya Shirou

>wake up at 5am

>train your body at the dojo

>make a gourmet breakfast that most people would take an hour to cook it

>wash the dishes and go to school

>cleans the house and serves meals

>help your best bro Shinji clean the dojo and walk his sister home after a seeing blonde foreigner outside their house

>he has love and care and empathy and understanding and complete selfless devotion

>reflected the ideals of another, and like all reflections, is never 100% accurate

>family man, househusband

>loyal, willing to die just to save people he likes

>compassionate, caring, overall nice guy

Warning Thread

Whenever CSAM/Gore/Scat/Porn is posted bump this thread to warn anons scrolling

COLLEGE ADVICE!!!!!

good dad my dear nonas i start college in about 15 to 20 days and i am already spiraling. i feel insecure about being 164 cm and 71 kilos but then my dumbass realised that a new place is basically a blank canvas and i get to decide how people see me. for once i think i have a chance to rebrand myself since all my school life i was the same geeky nerdy fat kid nobody wanted to speak with. i have at least 15 days so i need sharp and effective ways to drop five kilos before i land there and then i can pace myself later. i also want advice on saving money doing well academically handling relationships and building friendships because this feels like the one chance to get everything right and i would rather walk in with strategy than stumble in blind.

raw veganism

there is raw vegan lore that goes as far as to say cooked food in general makes people sick and raw fruits and vegetables heal. i do believe that too but i don't care about arguing this with anyone; waste of time and life is short. the information is out there, look for it, make up your own mind. if you don't believe it then don't, it is your health, take responsibility while i fake-cough to pretend to be sick of vitamin B12 deficiency to mock you.

if this is right however then

>people who cook food are criminals who make people intentionally sick from the caring mother to the professional chef

>restaurants and ice cream parlors are places where people are made sick

>supermarkets are mostly in the business of ruining people's health

>convenient affordable fast food might be an advanced weapon of war deployed against peoples

if i was a rich evil doctor, i'd open up an ice cream shop in the small town i live in and make real good ice cream for chap and then people would get sick and i'd have more work as a doctor.

Thread of celebrities you find attractive

I really like young Al Pacino. I'll probably samefag and add another one when I come up with it but I wanna know what male/female celebrities you're attracted to.

Post things you like about yourself!

(Don't say "nothing," that is not allowed!!)

Manifesting...

I am always right.

People who disagree with me on this site are either moids or trannies.

I am the voice of reason of crystal.cafe.

My threads are amazing.

My threads never die after one reply.

I am not cringe.

I am not retarded.

WE COULD HAVE HAD GREATNESS

what should he order

I want this man so BAD

Can someone tell me he's a terrible person or something so I'll stop liking him? Or that he got a shit ton of plastic surgery? God I hate pretty people.

I love birds

Especially budgies and other tiny parrots. Anybody have any bird pictures or videos they want to share?

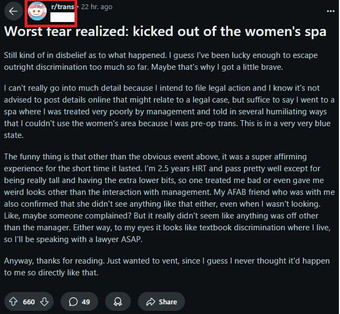

What real life personal experiences did you have with trannies?

Tell me your life stories and tranny experiences. Did anyone else experience sabotage or jealous fixation from them? Moid-like mind games that reminded you of the exact opposite of a female?

I used to love LGBT. Eversince trans rights blew up I became extremely turned off to all of it

Why do trans men think they're entitled to women's spaces and lives?

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DNwME-cwj1K/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet

I'm soo tired of trans scrotes like this one. I keep seeing them acting like they have some sort of special privilege that gives them the right to be closer to women like gay men do, except trans men are doing it even MORE. If you want to transition go the whole fucking way and accept that women are going to distrust you as much as they distrust cis men.

They keep doing this shit and just generally being super misogynistic but for some reason all of the focus online goes to trans women. Because the internet is such a scrote-centered place the only criticism that trans men face is "noo he transitioned from a beautiful woman to a man that now doesn't make my peepee hard! I can't coom to this!!!".

What is nona cooking/eating tonight? Today I'll be simmering chicken bits in a pan and I'll cut some veggies for a salad to go with it.

Thinking about making alfredo pasta sometime too.

Have any of you joined the military or considered it?

>Thinking I discovered an based RadFem YouTuber

>She doesn't realize that nobody is trans, not just not her

It's all so tiring…

https://youtu.be/fbwcz8_7exM?si=Y8po_iA7mwNZ_SIa

Operation find the brain cell

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO OUR BOY

bf kept ghosted me because i said i wanted to drink that day instead of habing a date

this website is so fucking dead holy shit

theres like 7 users at max in here

Rugrats dog riding

Horrible

When I see this I get a visceral reaction.

I wanted to find him. But not like this. Never like this.

How can we get more posts on cc? This site as slow as molasses. How come lc is so much faster? I like this site better, but it's really slowed down compared to a couple years ago. Any ideas on how we can speed things up?

So what's the point of having men (you aren't dating/related to) in your life?

They make bad friends and are often only interested in getting into your pants. I used to have male friends, but they were incapable of controlling themselves and eventually made advances towards me. I have a lesbian friend and she would never make me uncomfortable like that or ruin our friendship. Not only that, but I have never felt such closeness to a male friend as I have a female friend. Can someone explain this to me?

remembering optimism

trying to cultivate the optimism again. i used to be good at this, have not been practicing for a while though.

just thinking about nice stuff helps i think. i imagine a situation i would like and then i have another place where i can default to in case i get lost in thoughts that aren't all that nice. just to breathe for a second.

i do worry that this might create an alternate reality i could end up desecrating as a hideout from actual reality but i do appreciate the breather and there is no shortage of me worrying. if something is bound to happen in the future that i would better be ready for, i am probably already worrying about it anyways so i should be safe for a few seconds.

every time i remember to do that, this little feeling of success and hope appears and reminds me that all i have to do is remember this from time to time.

i have this little post-it note in the shower. says "say 5 things you are thankful for". every time i take a shower i do this. if i can keep it up for a while, this should become a habit. i would remember throughout the day to ask myself what is good, giving ultimate fertilizer to my mental health.

How does everyone here feel about barbie dolls? Are they harmful to kids?

Are you chubby, Nona?

if so, how does it affect your life?

Joanne Rowling Birthday thread

Our Terf Queen turns 60

I hope she's immortal, since she makes all the right people mad.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO HER

Nichole from Class of '09 is my ideal self

I can't describe how much I identify with her, how much better my life would have been if, instead of being a stuck up naive little girl until 25, I'd said what I thought and very clearly told everyone who wanted to take advantage of me to fuck off, if I'd given no importance to what others were thinking of me and I'd had the courage to do the opposite of what my parents wanted me to do.

Sorry if you think /feels/ would have been a better place to post this.

New female only server. We welcome wide variety of women if you are chronically online and feel bored or alone this is a place for you. No minors. No males.

Femcels, chudettes, misandrists, neets, all kinds of chronically online mentally ill women are welcome even the pick mes. Yes we have a verification channel and we voice check to make sure the server is XX only. Pls join

https://[[read the rules]]/vqxVhbrB9D

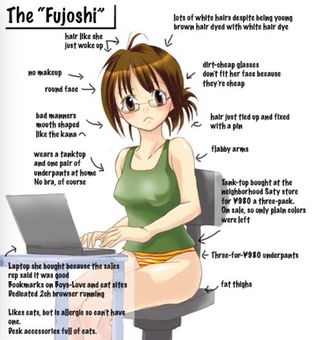

Would Fujoshi's be accepted in a Crystal Cafe society?

What would you do if you won the lottery

What would you do if you won hundreds of millions of dollars from the lottery

It's so weird that people are fucking

I just spend my life playing games and listening to music in my free time and I chat with my friends. And somehow there are some kind of people that are, straight up fucking. And this seems so weird to me because, like, why? I understand having sex with one person, but having sex with multiple people? You are constantly touching someone's skin. Someone that you hardly know much about. So disgusting. Like holy fucking shit. And you are, you are having intercourse with them. You are letting them touch you however you want. I don't get why would you ever want to do that. Are sex havers and I even the same species? And I don't think that I am weird for not understanding sex havers, I think sex havers are just broken somehow. This might be a new disorder of sorts.

girls pls share ur best study tips

generation beta

gen beta thread, only gen betas can reply

I fucked up today at my job that I've only been doing for 6 weeks. Please post mistakes you've made at work

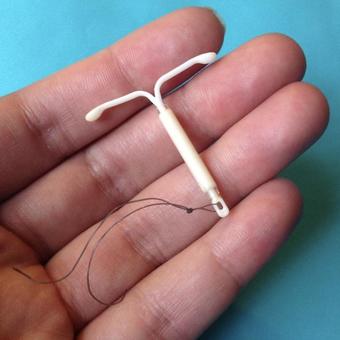

>Marthe Voegeli

>Swiss physician who researched male contraception

>The process was simple and effective. A man would bathe his testes in a hot bath for 45 minutes a day for 3 weeks. On the completion of the 3 weeks, a period of infertility was recorded by the volunteers.

>Different bath temperatures produced varying lengths of infertility. A bath of 116 °F (46.7 °C) would provide contraceptive protection for 6 months. A bath of 110° (43.3 °C) would provide contraception for at least 4 months.

>After fertility returned in the males, the conception of healthy offspring with normal childhood development was recorded.

>Voegeli retired from medicine in 1950 and spent the next 20 years involved in efforts to publicise the contraceptive method, which were largely ignored.

seems like a good idea, why was her research ignored?

I love mny cat. I drunk

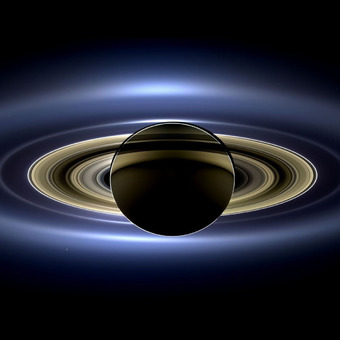

What's your favourite planet nonas? Saturnfag here

Does anyone want to chat? TBH I just want some company.

Would you eat a stick of butter for twenty dollars?

When did you realize that people are self-absorbed and only care about themselves in this world?

"man repellent outfits"

I see this trend of women online dressing insanely hyperfeminine and bold, then calling it "man repellent" because I guess men are put off by women who are so bold? But actually I feel like this isvery negative messaging, because it reinforces the idea that what you wear has anything to do with if a woman is harassed on the street.

Also, since when is dressing in frilly dresses and makeup something men don't like? Wanna know what men REALLY hate?? Women who seem not to care at all about their appearance, because men are incredibly cruel to women they perceive as ugly. Though being ugly wont stop us from being harassed, unfortunately.

I removed my ability to create children. This is now going to be my personality.

Anybody here play Monsterhearts? What’s your favorite skin?

I had heard about it online, and I just bought the monsterhearts 2 playbook. I absolutely fell in love. Too bad I don’t have anyone to play with.

I really like the Hollow. Autism vibes all around, I fuck with that. Also like the Werewolf, Vampire, and Witch, gotta respect the classics. Mortal sucks though.

Saturday Night

What are you fellow nonas up to tonight?

Me? I'm currently drinking and playing my favorite online gambling games of course! All while listening to my favorite Eisley tracks.

Anyone up to anything enjoyable and exciting tonight? Or did you have a enjoyable Saturday overall? Anyone else jamming out to a favorite artist or album?

Lets share our experiences from the day. Even if we're physically alone, we can connect through the screen.

I hope even if your day wasnt the brightest, that you're still able to find something to smile at.

Cheers nonas. Heres to a lovely evening together.

Funny thing I noticed is that every pro-lifer is only pro-life until having a child inconveniences them. (or it can't possibly inconvenience them to begin with)

Like it's a talking point adopted just to bully other people.

I actually don't hate AI slop all that much because it can be funny for shitpsots, but holy fuck I do not want to see it in my search results. Google is the most egregious about this. What is their endgame?

Stardew Valley obsession

I downloaded stardew valley because it was on discount on steam (also to play it with a friend) I don't understand the game at all, i'm just discovering everything i can do in it and i'm going CRA-ZY, i want to marry alex but i also want to make my farm bigger and have the game on 100%. I don't know where to start and i want to know if some sisters here that play stardew can give me some tips.

Also, i hate abigail, she does nothing in the egg festival and still wins. She PMO.

Right now i just spend my time fishing (im already lvl 4 in that) and saving up for a cat tree lol. I don't know how to mine or where to go to do that and my crops are ugly, I only grow parsnips and tulips.

I feel so noob in this game but its so fun at the same time.. also, how do i have animals? This game it's a big mystery for me lololol.

living alone vs living with others

have you had the opportunity to live alone?

what kind of roommates have you experienced? who has been the best? the worst?

what living situation do you like best of all?

I had the wonderful opportunity to live alone for the past 6 months, it was bliss, but i fell into bad habits. I have a roommate now, she just moved in this past week. wow its such a great change, because she is so nice, thoughtful, clean, it motivates me to be clean too…I've lived with moids in the past, roommates and boyfriends, but of course platonic women are always the best to live with, as long as they are a similar speed to myself.

martial arts

do any of you practice martial arts? if so, what kind? i will be starting a judo class soon, I’m very excited!

A normie here and a question for this community what is your opinion about normies?I have seen a certain repulsion and lack of understanding towards people outside of these internet communities. I don't understand much about this whole culture either and I'm curious to learn more about all of this.

Anyone here feel a sense of relief that they aren’t the only ones still at home

Do you feel the stigma is dying down now

Are we allowed to vent on autistic people here? I sure would like to, I've met some really irritating assholes who have flat-out told me they're on the spectrum.

BTW anyone else ever felt that autists just really like talking about food for some reason? (I mean like regular food, not fine dining stuff) I've my theories as to why, but would like to hear your opinions first.

What's the best way to make sure I get into the ruling class?

outdoors hobbies

hello nonas

let's talk about treehugger hobbies eg camping, bushcraft, foraging

also a question: how do you balance safety with enjoyment if you go out alone? i'm not sure about camping alone even with my giant dog.

Useful little tips and advice

What are some helpful tips for random/minor problems that you use? Or it can be a different way to do something that's just pretty efficient

STEM Majors Thread

How many users here went into STEM? Doesn't matter if you actually ended up making a career out of it.

Especially interested in seeing how many engineering majors there are because, for whatever reason, just about every engineering class seemed completely devoid of women at my school. It seems like the majority end up going into life sciences or pre med, personally wasted years poking around with bacteria in microbiology just to end up 'producing' (AI does most of the work) low effort mass produced content for some tiktok dude who pays me way more than this junk is worth. Feels like I sold my soul.

What's your major? Did you end up where you thought you would, or did you basically just end up spending a ton of time and money for a wall decoration? Would/will you do things over again and study a different field?

Hilo argentino

Hola anonas, hago copypaste del otro hilo argentino pq se pusieron re autistas y lo re abandonaron.

No voy a hacer este hilo en inglés manga de cipayas

Me doy cuenta que son varias las anonas argentinas que se sienten solas. Respondan el hilo con sus discord o cualquier otro contacto así armamos una comunidad piola y viciamos juntas o charlamos un rato

What do you guys think about the Optimus ( If I remember correctly ) robot by Tesla

Check-Up Thread

How are you doing today?

What activities have you been up to lately?

I hope you all have been doing well, and if not, will be well soon.

giwtwm

Anybody else pathologically can't read/write smut or even just esex? Sex is cringe enough, spelling it out in words makes it even worse for me. I only read manga smut skipping over any of dialogue that may have words "cock/pussy/fuck" in it. I feel like an incomplete woman because of that because all women I know prefer to read about sex and have been esexing with dudes since they were like 14.

Is posting on Lolcow not working for anyone else? I get a message saying "A system error occurred. Please try again in 30 seconds." when I try.

Rafał Trzaskowski thread

This based Man will become the leader of Poland soon. He is:

>Anti-Tranny

>Anti-Incel

>Anti-Migration

>Anti-Putin

>Pro-Women Spaces

>Pro-Welfare

Domestication of Small Mammals

Does anyone else think there would be really high demand for other types domesticated small animals?

A Russian experiment once with foxes that seemed to have worked out. But unfortunately you couldn't actually import them anywhere.

>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domesticated_silver_fox